Peter Thiel has famously argued that failure often doesn’t teach us much; he calls failure “massively overrated,” noting that it’s hard to learn from failures because they usually result from many factors, not just one, which makes drawing useful lessons difficult [Peter Thiel on How to Think for Yourself | Q&A on The Tim Ferriss Show].

Taken out of context, this viewpoint can be quite controversial and may even offend the most dedicated entrepreneurs. Certainly, the statement can be argued both ways, and to avoid ambiguity, this article explores both perspectives.

When a startup fails, the consequences are devastating; for founders and owners, investors, and customers alike. Learning from an outcome like a shutdown requires more than technical and commercial involvement; you must measure both success and failure in enough detail to extract actionable insights that benefit future investor-backed ventures and inform customers’ future supplier decisions.

Lean Startup Concept

Eric Ries’s book The Lean Startup introduces a methodology for continuously evaluating your technology, product, and service in the market. The goal? Ensure sufficient iteration to validate demand and success. However, this framework primarily addresses distribution risk. In reality, startups face both technology risk and distribution risk, and both must be addressed to minimize the chance of catastrophic failure.

What Is an MVP?

Ries provides a detailed guide for defining the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), a version of the product with just enough features to begin learning from users and reduce distribution risk (specifically, gathering data on Product–Market Fit). Essentially, an MVP is the smallest effort needed to test a concept in the market and collect meaningful feedback from customers.

Metrics for the MVP

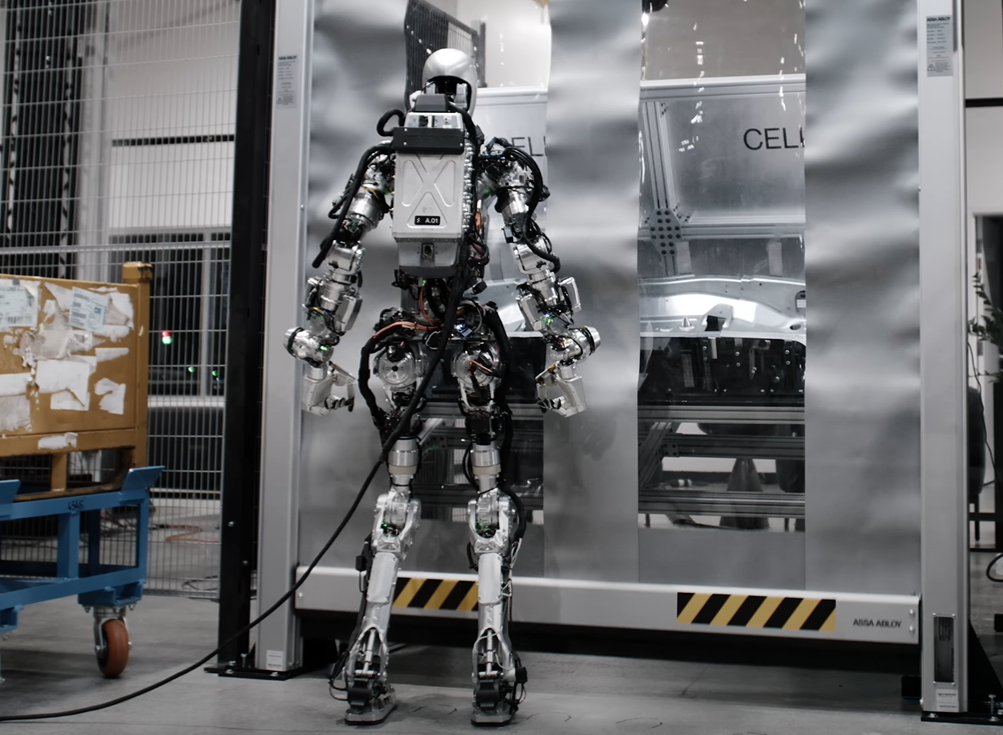

When gathering feedback from potential customers or partners, should you implement all suggestions equally? Not necessarily. Even in complex systems, applying common sense matters. Focus on target (or “beachhead”) markets: verticals where adoption is expected to climb fastest and pave the way for broader traction. You can learn more about this in discussions of “crossing the chasm“. Define metrics that clarify which feedback matters most. If customers are suggesting adjustments to a product (for example, changing robot size) it likely makes no sense to prioritize suggestions like color preferences at that stage.

Technology Fit vs. Distribution Fit: What Matters More?

Startups fail for many reasons. That’s part of the problem, there are too many factors that can go wrong and too few consistent paths to success. Here, we focus on the core ideas from Sebastian Mallaby’s The Power Law, which emphasizes technology risk and distribution risk as the most critical.

- Technology risk primarily arises early in a startup’s life. It’s not usually about the entrepreneur’s capabilities, but about the roadmap itself; whether it’s too ambitious, aggressive, or unrealistic. That’s why defining and testing an MVP early is essential. These risks can be tracked using measures like Technology Readiness Levels (TRL), estimated hours, budget, and realistic timelines to reach milestones.

- Distribution risk becomes more visible once technical risks are under control. It’s about generating revenue, finding ways to minimize effort while maximizing profit. Metrics for this are largely financial. Benchmark data is a helpful starting point, but the key is customizing those benchmarks to your specific product and vertical. By obsessively tracking these metrics, you can detect failure signals early and “stop digging the startups hole.”

What if We Do All This and Still Fail?

Despite best efforts, most startups still fail, often because they run out of cash. To extend runway, the risk–reward balance must appeal to investors, and that requires credible metrics:

- Technology risk: Learn from misjudging TRL goals.

- Distribution risk: Learn from failing to consult the right influencers or channels.

Devastation, Emotions, and the Value of Persistence

Failure can be devastating, especially proportional to the time, tears, and energy invested. That’s why knowing when to pause or stop is as critical as pushing forward. Yes, around 90% of startups fail, but virtually 100% of people who keep trying eventually succeed in some way in life and business. The secret lies in persistence: focus on one project at a time, stop when needed, reflect, learn, and then either resume or pivot until you find something that works.